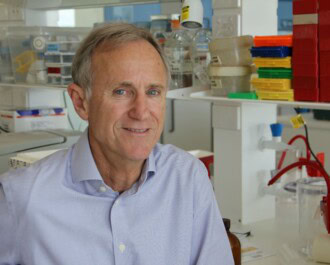

Researchers at Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre are calling for greater caution in genetic testing for familial breast cancer, warning of the potential of ‘false red flags’ being raised.

In a paper published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, the Peter Mac team has demonstrated that some genetic tests for breast cancer may be misinterpreted, potentially misinforming the affected families and risking unnecessary preventive treatments.

“It is now possible to screen a large number of genes at the same time – known as panel testing – at a fraction of the cost previously required to sequence just one cancer-causing gene such as BRCA1,” according to Professor Ian Campbell, Head of Peter Mac’s Genetic Cancer Research Laboratory.

“Understandably, this has increased demand for such tests amongst health care providers and patients concerned about their family history.

“However, while the increased risk of breast cancer associated with some genetic mutations is proven, for others there is a lack of robust scientific data to suggest preventative treatments are required.”

Peter Mac researchers assessed 2,000 women who had been diagnosed with breast cancer and then referred for genetic testing because of a strong family history of the disease. Their genetic make-up was compared to a control group of 2,000 women who did not have breast cancer and who were drawn from the Lifepool research study funded by National Breast Cancer Foundation.

Each group was tested for 18 genes on existing panels offered by commercial providers, and the results showed very few differences in gene sequence once the major cancer-causing genes (BRCA1 and BRCA2) were accounted for.

Only two other genes – TP53 and PALB2 – were more commonly mutated in the cancer-affected group versus the control group, both of which are well known to increase cancer risk.

Professor Campbell said the study confirmed there is limited scientific evidence that many of the other genes incorporated in panel tests play any role in cancer risk.

“The results supported our hypothesis that panel testing can be incredibly powerful and predictive when there is prior evidence that mutations in particular genes – such as BRCA1, BRCA2, TP53 and PALB2 – are cancer-causing.

“However, we’ve also shown that doctors and patients should exercise extreme caution in acting on other gene mutations detected on panel tests, when there is no proven risk of a hereditary cancer link.”

Professor Campbell said patients should be given information alongside their test results indicating the prevalence and quality of research associated with each gene included in their panel test.

“Where there is concern, consultation with a qualified familial cancer expert is strongly recommended,” Prof Campbell said.

“Without this, there is real potential of the test raising false red flags and that preventative treatments are undertaken when there is no evidence of additional risk.”

Professor Campbell says it also is essential that funders and conductors of genetic research demand the highest quality standards, and adhere to robust rules regarding levels of evidence required – particularly comparison to control populations – before any test is made available in a clinical setting.

Jackie Coles, acting CEO of the National Breast Cancer Foundation, says, “The results of this study are a reminder that although we’re always striving to better understand the genetic patterns of breast cancer development, we must be able to use that knowledge correctly and effectively if we’re to get the best outcome for each individual affected by the disease.”

Krystal Barter, CEO and founder of Pink Hope, says, “We know BRCA gene mutations are linked with a much higher risk of certain cancers and as an organisation we help families know their risk and change their future, but what do these lesser known gene mutations mean? Only time and more research will tell us this.”

Anyone concerned about their personal risk of cancer, including those with a family history of the disease, should discuss this with their GP or contact their local familial cancer centre which can provide information.

More News Articles

View all News