Prevent

Prevent

The majority of breast cancer cases occur in people with little or no family history. However, about 5-10% of breast cancer cases are considered to be hereditary, caused by abnormal genes passed from parent to child. There has been significant publicity regarding the link between BRCA1/BRCA2 gene mutations and familial breast cancer; however, these mutations explain less than half of all inherited breast cancers.

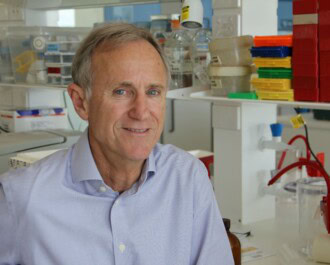

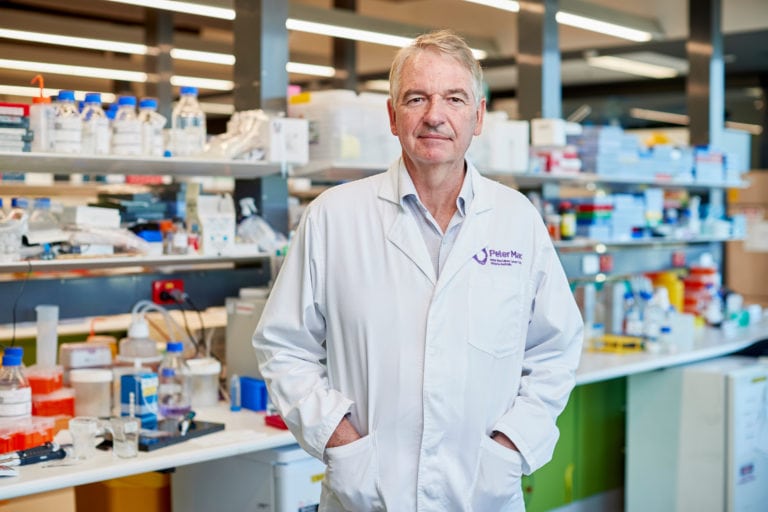

Significant research is underway to determine which other genetic mutations could make women more likely to develop breast cancer. One such study, led by Professor Ian Campbell (Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, and the University of Melbourne), has recently uncovered another piece of the puzzle.

Professor Ian Campbell, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre

Professor Campbell and his team investigated the gene RAD51C, which was previously known to be associated with familial ovarian cancer. To determine whether it also played a role in breast cancer was challenging; disease-causing mutations in the gene are very rare (occurring in less than 0.5% of women), which means large study populations are needed to investigate any association.

To overcome these challenges, Professor Campbell’s team sequenced the RAD51C gene from almost 8000 women involved in two large Australian studies. Samples from women with hereditary breast cancer were analysed from the Variants in Practice Study (3080 cases), while samples from population-matched cancer-free women were sequenced from the Lifepool study (4840 controls). The samples from women with hereditary breast cancer were known not to have any BRCA1/2 disease-causing mutations.

The results, published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, showed that although disease-causing RAD51C mutations were very rare in both groups, they were much more common in the women with breast cancer (0.4%; 11 of 3080 cases) than those without (0.04%; 2 of 4840 controls). The tumours of the women with RAD51C mutations were also more likely to be triple negative breast cancer, which is more challenging to treat.

“These findings have the potential to help women, who are highly predisposed to breast cancer, effectively manage their breast cancer risk,” said Professor Campbell. “We will now continue to investigate another 40 genes that we suspect could be linked to breast cancer, to try and complete more of this puzzle.”

This work was co-funded by NBCF and Cancer Australia, through the Priority-Driven Collaborative Cancer Research Scheme.

More News Articles

View all News Prevent

Prevent