Human breast tissue is extraordinary, undergoing dramatic remodelling from childhood, through puberty and adulthood. One of the most amazing processes enables mammary glands to produce and transport breastmilk whilst breastfeeding, and then return back to a resting state after a child is weaned. Now, Melbourne researchers have discovered the cells that allow this miraculous transformation, and are learning more about how they may contribute to breast cancer.

Scientists from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute in Melbourne have identified new immune cells in the breast tissue, which they have named ductal macrophages, or ‘DMs’. Macrophages are a specialised immune cell type found in the body that “eat” foreign invaders (bacteria, viruses) and sick or dead cells.

The team, headed by NBCF-funded researchers Professor Jane Visvader, Dr Anne Rios and Professor Geoff Lindeman, discovered that the DM cells play an essential role in the removal of milk-producing cells after breast-feeding ends. This is particularly impressive given that milk-producing cells are very large, containing twice the normal amount of DNA.

The researchers used 3D microscopic images of breast tissue to identify the DM cells, and then videoed their behaviour in tissue that was converting from a lactating to a resting state. Lead author, Dr Caleb Dawson, explained that they were then able to view the cells in fine detail.

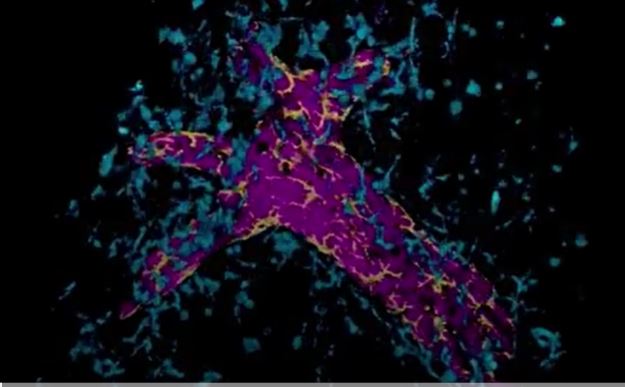

Immune cells called macrophages are important for mammary gland formation and function. This show a mammary gland duct (purple), surrounded by collagen fibres (pink) and macrophage populations (yellow and blue). The yellow macrophages are breast-specific ductal macrophages (‘DMs’) that live on the ducts and survey the epithelium with their arms. CREDIT

Dr Caleb Dawson, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research

“Shaped like tiny stars, these macrophages form a network that covers mammary ducts. They don’t move around the ducts, but each DM cell has many tiny arms that it uses to monitor the ducts and protect them from damage,” said Dr Dawson. “We saw that the DMs were waiting on top of the milk-producing cells monitoring for damage, and as soon as they died, the DM’s ate them.”

Whilst DMs are important for keeping breast tissue healthy in these situations, there is also evidence that they might have negative effects in women with breast cancer. The researchers found that breast cancer tumours are able to manipulate the DM cells, forcing them to assist with cancer spread throughout the body.

“Ductal macrophages are spread throughout the mammary ducts. As cancer grows, these macrophages also increase in number,” Dr Dawson says.

“We suspect that there’s the potential for ductal macrophages to inadvertently dampen the body’s immune response to cancer. This would have dangerous implications for the growth and spread of cancer in these already prone sites and would affect cancer treatments.”

On the positive side, the role of these cells also provides researchers with another potential treatment for breast cancer. It is possible that blocking the activity of DMs in women with breast cancer could slow or stop the progression of the tumour. Future work will now investigate the future potentials for these exciting findings.

This work was partly funded by NBCF and has just been published in the prestigious journal Nature Cell Biology.

More News Articles

View all News