You have returned to the top of the page.

The spread of breast cancer, a process called metastasis, is the cause of death in nearly all patients who die of breast cancer.

Around a third of those diagnosed with breast cancer will later develop metastatic breast cancer, but as yet there is no way to know which patients will or when it might occur.

Metastasis may happen up to 20 years after treatment for the original tumour, causing ongoing fear and anxiety for patients and their families about when or if the disease might come back.

Metastasis may happen up to 20 years after treatment for the original tumour, causing ongoing fear and anxiety for patients and their families about when or if the disease might come back.

Cancer cells can spread from the primary tumour and lodge in other tissues in the body, such as the bone marrow, and remain alive but not increase in number for many years – a process called metastatic dormancy.

Researchers have not yet discovered how a cell can stay alive but not divide and grow, and why it suddenly starts growing into a detectable secondary cancer.

The aim of this NBCF-funded project is to explore the role of a gene called c-Myc that can potentially control the dormancy of tumour cells and develop ways of  turning this gene on and off and test the ability of a cancer cell to stay dormant.

Professor Robin Anderson and her team are looking to see if dormant tumour cells use c-Myc to preserve their survival until conditions in the body are ideal to support rapid growth into a secondary tumour.

Until now, research into metastatic dormancy has been hampered by the lack of good ways in which to study the process, so Professor Anderson’s study has the potential for a breakthrough in understanding about how cancer returns and ultimately how to stop it.

Women with breast cancer often have additional physical and psychological stresses to cope with during their treatment, many of which are preventable. For example, two thirds of those who are hospitalised with advanced metastatic breast cancer will have a delirium episode at some point during a stay in hospital.

Delirium is a serious medical condition affecting the brain, which results in confused thinking and reduced awareness of environment. It also impacts the ability to communicate at a critical time when being mentally aware and interacting with loved ones is crucial for quality of life.

Women with advanced metastatic breast cancer are at higher risk of delirium due to medical problems such as changes in blood levels of calcium or oxygen, infections, and the side effects of their medications. Each year it is estimated that at least 2000 women with advanced breast cancer experienced delirium before their death during a hospital stay. Delirium is reversible in only half of cases and there is no medication to effectively treat its symptoms.

Delirium is one of the most significant medical complications for those in the final stages of breast cancer. It has serious adverse consequences: it is highly distressing to experience for the person themselves and to witness as a family member, it increases the risk of complication in hospital such as falls, reduced independence and function and cognitive capacity, and is associated with longer hospital stays, higher health care costs and a high mortality rate.

The good news is that delirium is preventable in many cases and recent research has shown that incidences of delirium in older hospitalised adults can be reduced by up to 50 per cent. Additional data is needed specifically for the women with advanced metastatic breast cancer which takes into account other factors such as fatigue and/or limited mobility.

Professor Meera Agar

NBCF-funded Professor Meera Agar and her team will run a trial to collect data on the benefits of methods to avoid delirium episodes. These methods include ensuring they get enough sleep, enhancing physical function, maximising hydration and nutrition and making sure patients are not isolated from sounds and senses which help to keep them grounded.

Professor Agar’s research program aims to reduce the incidence of delirium in women with advanced metastatic breast cancer by 50 per cent, a change which would mean a significant improvement to their quality and length of life.

Research has improved the success rate of breast cancer to 90 per cent, but for women with metastatic breast cancer (when the cancer has spread beyond the breast) modern treatments are only able to prolong life, not stop the cancer progressing.

Targeted therapies are a new class of medicines that have improved the survival and quality of life of breast cancer patients. Targeted therapies are among the last treatment options for metastatic breast cancer patients in the very advanced stages of the disease, and while some patients experience substantial benefit from these medicines, unfortunately, many others either do not respond or experience severe toxicity.

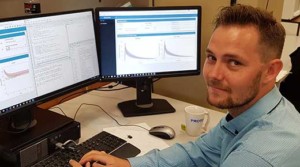

In this project, Dr Ashley Hopkins will use advanced mathematical techniques aiming to identify predictors of good and bad outcomes to targeted therapies used

in metastatic breast cancer. Dr Hopkins will analyse data that has been collected across a series of clinical trials on targeted therapies to determine who responded well and why, so these drugs can be more accurately prescribed.

In this project, Dr Ashley Hopkins will use advanced mathematical techniques aiming to identify predictors of good and bad outcomes to targeted therapies used

in metastatic breast cancer. Dr Hopkins will analyse data that has been collected across a series of clinical trials on targeted therapies to determine who responded well and why, so these drugs can be more accurately prescribed.

Dr Hopkins intends to share the study results so that clinicians and breast cancer patients can assess the benefit and risks of these treatments – such as the likelihood of a positive outcome weighed up against the drugs toxicity.

This type of information can help guide treatment decisions that may improve response rates and decrease toxicity to specific therapies, provide an indicator of when to use alternate therapies or focus on palliative care, which may also lengthen the survival of cancer sufferers.

If the success rates of targeted therapies can be improved, they could be included as options in standard care within the next 10 years, helping to successfully treat women with metastatic breast cancer.

Olaparib is known to be effective treatment for breast and ovarian cancers in people with inherited mutations. Many more patients do not have a genetic risk but have cancers arising from spontaneous mutations. Our clinical trial aims to find out whether olaparib benefits patients with breast or ovarian cancers with non-inherited mutations or abnormalities.

Altered metabolism is a key feature of cancer, with metabolic pathways reprogramed to meet the energy demands of cancer cell growth. However, little is known about the role of increased lipid metabolism in breast cancer. We now show that ACC1, a key regulator of lipid metabolism, is expressed by breast tumours, and that inhibiting ACC1 impairs breast cancer progression. This proposal will validate and characterise ACC1 as a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of breast cancer.

Three quarters of breast cancers are estrogen receptor positive (ER+), and although current treatments (such as tamoxifen) are extremely effective, more patients die from this type of breast cancer than any other form of the disease. Indeed, for some women with ER+ breast cancer, their tumours develop resistance to therapy and their cancer returns.

Dr Iza Denis

NBCF Post-doctoral Fellow Dr Iza Denis believes this is due to an imbalance between two other female hormones that are naturally found in breast cells, called androgen and progesterone, which when combined with estrogen participate in the normal development of the breast.

Identifying the interactions between estrogen, androgen and progesterone could be critical to understanding treatment resistance and how to overcome it, but there is currently little information on the role that they might play.

This project will use advanced genomic profiling techniques to generate information on female hormone interactions in normal and malignant human breast tissues.

This could ultimately lead to the identification of biomarkers that are able to determine the women who will most benefit from treatment, and those that are most at risk of their breast cancer returning.

Knowing how each woman may respond to treatment enables health professionals to tailor a treatment plan that specifically matches the makeup of her particular tumour to the best available therapy with the least side effects – a growing field of medicine called personalized medicine.

Seventy per cent of breast cancers are fuelled by the female hormone estrogen and thanks to advances in medical research and healthcare these women receive treatments, such as tamoxifen, that significantly reduce their risk of the breast cancer returning later in life.

However, around a third of women have what is called hormone treatment resistance, meaning their breast cancer doesn’t respond to treatment.

It’s a big challenge as there is currently no way to determine at diagnosis if a woman will be resistant to treatment. If she resistant to treatment, other effective options are very limited and life expectancy is short, around two years.

Professor Susan Clark

Overcoming treatment resistance and paving the way for better outcomes for these women is the focus of research being led by NBCF-funded Professor Susan Clark.

Professor Clark and her team aim to determine for the first time which types of genetic mutations trigger changes in the tumour DNA’s internal structure and are responsible for treatment resistance.

Her study aims to identify markers that will help tell if women are hormone treatment resistant when they are diagnosed. This information could be used to personalise the management of their care from the outset and potentially avoid women undergoing treatments that won’t work.

This research also intends to test potential avenues for effective alternative treatments for that could overcome treatment resistance and save the lives of thousands of women.

Metastatic breast cancer – when the tumour spreads beyond the breast to vital organs in the body – is treatable but largely incurable and is the cause of 90 per cent of breast cancer deaths.

A major challenge in treating metastatic disease is that an effective treatment for one metastatic site (e.g. liver, brain or bones) may be less effective for other metastatic sites.

This may be explained by increasing evidence which indicates that breast cancer tumours located at different sites in the body could each have a different genetic make-up, rather than being genetic clones of each other.

These genetic differences within a single patient can have major impact on their response to therapy and how the cancer progresses. A better understanding of what is happening at the genetic level for each tumour is an initial, critical step before more effective treatments for metastatic breast cancer can be developed.

Dr Niantao Deng

NBCF-funded Dr Niantao Deng is investigating how metastatic breast cancer progresses throughout the body. In a pioneering area of medical research he is analysing the genes of tumours that have been donated by breast cancer patients and collected shortly after their death. The importance of this process is that tumour samples from multiple metastatic sites in one person can be analysed for their genetic differences, an opportunity which is not feasible in living patients.

A portion of each tumour is then put into mice which are then tested with different treatments to determine which is most effective.

The findings from this study have the potential to greatly improve treatment for metastatic breast cancer by helping to predict breast cancer patients’ response to therapy. Dr Deng also aims to pave the way for more effective treatment strategies for metastatic cancer to help those affected live longer, better lives.

Women with metastatic breast cancer are dying from the disease because no treatments have yet been developed that can stop tumour growth once it spreads beyond the breast.

The standard treatments currently available for women with metastatic breast cancer can prolong life, but ultimately do not prevent death. These treatments include toxic chemotherapy which, although initially effective at killing cancer cells, simultaneously attacks some healthy cells and causes unpleasant side effects.

Dr Kylie Wagstaff

In this four-year NBCF-funded study, Dr Kylie Wagstaff is aiming to find a specific biomarker that differentiates healthy cells from cancer cells. This discovery could firstly lead to easier and more accurate detection of metastatic breast cancer and, secondly, aid the development of drugs that recognise and target only cancer cells.

The new treatment would be much more effective, while also significantly reducing the harmful side effects women experience as a result of standard breast cancer care. This much-needed improvement in treatment for women with metastatic breast cancer could mean better prognosis and greatly enhanced quality of life during treatment.

The vast majority of women with breast cancer have oestrogen-receptor positive tumours. After their surgery, these patients will almost always be treated with endocrine however not all will require chemotherapy.

This decision is usually based on an assessment of risk factors related to the tumour, its biology and the patient. There are multiple tests available that can help clinicians and patients to determine what the risk is of the cancer relapsing. One such test is called the Oncotype DX Recurrence Score. This test is very expensive (approximately $4000) and it not funded by Medicare and therefore remains inaccessible to most patients. This study evaluates a novel test called the IHC4+C score which estimates risk of the cancer coming back. For example, a risk score of 5% means that there is a 5% risk that the cancer could come back over the next ten years if the patient takes their endocrine therapy (and does not have chemotherapy). This score helps to decide whether chemotherapy should be recommended.

In the case of a score being 5%, this is considered a low risk score; hence it is unlikely that chemotherapy would be recommended to this patient. This test has been shown to provide similar information to the Oncotype DX but has the advantage of being affordable and routinely available. When used to help make treatment decisions, this test has been shown to result in less patients requiring chemotherapy.