Researchers in the UK have found that breast cancer can recur and spread to other parts of the body 20 years after treatment.

The research, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, collected data from more than 60,000 women who had been diagnosed with hormone sensitive breast cancer (oestrogen receptor positive or ER+breast cancer). Current treatments for this type of breast cancer are anti-oestrogen therapies tamoxifen and aramotose inhibitors, which often cause undesirable side effects like early menopause. These treatments are usually taken for five years, but in some cases longer.

What the researchers found

The results of the study highlighted how important it is for women with ER+ breast cancer to persevere and continue with anti-oestrogen treatment for longer than the recommended five years: 11,000 women had their cancer return and spread to other parts of the body (also known as metastatic breast cancer) in the 15 years after stopping treatment. It also showed that the risk of cancer coming back remained the same year on year from when they concluded treatment to 15 years later. Importantly, those with breast cancer that had spread to four or more lymph nodes had the highest risk of their cancer coming back 20 years after diagnosis.

Although knowledge and understanding of breast cancer has come a long way and resulted in substantial improvements in the treatment of breast cancer, there is still much work to be done in order for researchers to better predict when and why breast cancer returns.

Unlocking the mystery of breast cancer relapse

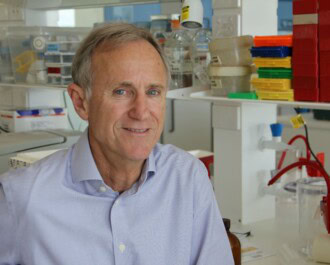

NBCF funded researcher Associate Professor Therese Becker from the Ingham Institute is conducting vital work to unlock the mystery of why breast cancer returns and metastasises, sometimes after many years.

Metastasis occurs when solid cancers release cells, called circulating tumour cells (CTCs), into the blood stream which then resettle at distant organs and form more tumours. For a long time, many CTCs just stay dormant without growing into a harmful tumour. However, sometimes these cells can wake up and change into rapidly growing tumour cells. This change from dormant cells to metastatic cells is currently not well understood.

A/Prof Becker’s project aims to identify the genes that cause the change from dormant to metastatic cancer cells and to understand potential triggers for the change.

This knowledge will have two important potential outcomes for breast cancer patients; it will enable A/Prof Becker’s team to develop a blood test to monitor potentially emerging metastatic CTCs in breast cancer survivors which will help ensure they receive treatment in time. It could also lead to potential avenues for developing therapies that would prevent CTCs from switching from a dormant state into metastatic disease.

More News Articles

View all News