When breast cancer patients get chemotherapy before surgery to remove their tumour, it can make remaining malignant cells spread to distant sites, resulting in incurable metastatic cancer, according to the results of a new study.

The main goal of pre-operative (neoadjuvant) chemotherapy for breast cancer is to shrink tumours so women can have a lumpectomy rather than a more invasive mastectomy. It was therefore initially used only on large tumours after being introduced about 25 years ago. But as fewer and fewer women were diagnosed with large breast tumours, pre-op chemo began to be used in patients with smaller cancers, too, in the hope that it would extend survival.

But pre-op chemo can, instead, promote metastasis, scientists concluded from experiments in lab mice and human tissue, published in Science Translational Medicine.

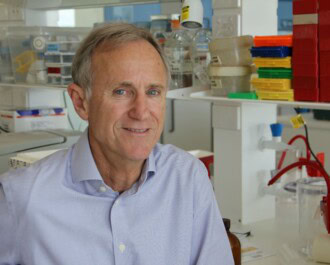

The reason is that standard pre-op chemotherapies for breast cancer affect the body’s on-ramps to the highways of metastasis (the spread of cancer to other parts of the body), said biologist John Condeelis of Albert Einstein College of Medicine, senior author of the new study.

Called ‘tumour microenvironments of metastasis’, these on-ramps are sites on blood vessels that special immune cells flock to. If the immune cells hook up with a tumour cell, they usher it into a blood vessel. Since blood vessels are the highways to distant organs, the result is metastasis.

What the study found about metastasis

As part of the study, the scientists analysed tissue from 20 breast cancer patients who had undergone pre-op chemo (12 weeks of paclitaxel and four of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide). Compared to before the chemo, the tumour microenvironment after treatment was more conducive to metastasis in most patients. In five, it got more than five times worse. No patient’s microenvironment got less friendly to metastasis.

But fortunately, not all breast cancer patients have the kind of tumour microenvironment in which pre-op chemo can promote metastasis.

A drug that is still in development may be able to block the on-ramp to the metastasis highway and these same scientists are also investigating if it can improve outcomes in metastatic breast cancer.

This an abridged version of an article originally published on statnews.com

NBCF note: We have received a number of enquiries from the general public regarding this story. NBCF would like to clarify that the article reports results obtained from studies in laboratory mice as well as a small number of patient tissue samples. In small studies such as this it is often difficult to extrapolate results to clinical care and it is unclear what the clinical significance of this study may be at this early stage. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is an effective and internationally accepted treatment for breast cancer, particularly for triple negative and HER2-positive breast cancer, and patient outcomes do not differ when compared to adjuvant chemotherapy in multiple large patient studies (Level 1 evidence). Women and men affected by breast cancer should always refer to their treating physician to discuss what treatment options are best for their specific situation.

More News Articles

View all News