A multidisciplinary team, based largely at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, has recently published the largest and most comprehensive “cell atlas” of breast tissue to date.

One of the challenges in breast cancer research is that breast tissue is highly complex, containing a wide range of cell types. These cells include ductal cells for milk production and release, connective tissue cells and immune cells. Different cancers can arise from the various types of ductal cells, making it important for researchers to know the characteristics of all breast cell types.

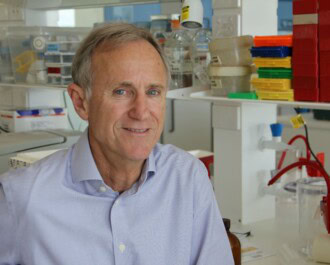

The new study, led by NBCF-funded researcher Professor Jane Visvader, used a technique known as “single cell transcriptomics” to investigate the gene expression in over 340,000 individual cells from breast tissue samples. These samples included healthy, pre-cancerous and cancerous tissue, enabling the team to determine changes in cell composition between them.

“Different types of breast cancer arise from distinct precursor cells. However, breast cancer development can be impacted by other cells within the breast,” Prof Visvader explained. “This atlas provides a high-resolution view into the various cell types that make up breast tissue in different states and a blueprint for studying changes that lead to breast cancer.”

The study discovered a number of important findings, including that one subset of cells in healthy tissue are altered when a woman enters menopause. In cancerous tissue, the team discovered that hormone-responsive cancers contained fewer ‘activated’ cells of a specific immune type. This could explain why many of these tumours are less responsive to anti-cancer immunotherapies.

The research incorporated expertise from a number of fields, including breast cancer biology, bioinformatics and oncology. The findings were published in May in the EMBO journal, with the atlas now freely available to researchers globally.

“This will be an invaluable resource for breast cancer researchers around the world,” said Prof Visvader. “Our research has important implications for not only understanding how breast cancers arise but also how cells in the surrounding environment contribute to their development, spread and response to treatment.”

More News Articles

View all News