A new three-dimensional high-resolution imaging technique will allow researchers to obtain a closer look at the cells within a breast cancer tumour. This is the first time that researchers have been able to visualise individual clones, known as ‘sister’ cells, which descend from a single pre-cancerous cell.

Researchers at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research published the results of their study in Cancer Cell this week, showing that the technique was able to distinguish cells at different evolutionary stages. This allows determination of how a pre-cancerous cell can develop into a tumour. In addition, the imaging allows observation of how the cancer cells change structure over time to become resistant to cancer treatment drugs.

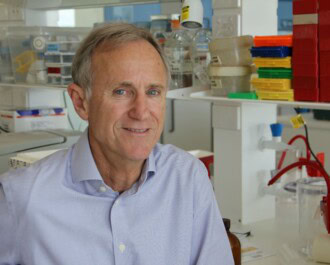

The study, led by Dr Anne Rios with Professors Jane Visvader and Geoff Lindeman, discovered that pre-cancerous cells rarely develop into cancer. However, in the cells that did become cancerous, they saw highly changeable features, which allow the cells to become resistant to certain therapies.

“Once a tumour has formed, we discovered it was very likely for its cells to undergo a so-called ‘epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition’ (EMT). This is a change within the cell, transforming it from an ‘epithelial’ form, to a ‘mesenchymal’ form that could have a growth advantage,” Professor Visvader explained. “Our models suggest that EMT is not a rare event but is an inherent feature of mammary tumour cells.”

The imaging studies have been completed in laboratory models for now, but the researchers suspect that human breast cancer cells will also demonstrate this high rate of EMT.

“If EMT frequently occurs in human breast cancers, it means the cells are a ‘moving target’ – they can evade one set of weapons we have to fight the cancer, meaning we need to develop strategies that are more broadly targeted,” said Professor Lindeman.

As well as providing these new insights into the ways that cancer cells develop, the new imaging technique will be applicable for many other research studies.

“Until now it has been challenging to visualise the intricate structures of complex tissues such as breast tissue, or to see the true arrangement of cells within tumours,” Dr Rios said. “This new, rapid way to prepare tissue samples retains their intricate architecture but allows us to distinguish individual cells and the three-dimensional structure of the tissue.”

The study was proudly supported by the National Breast Cancer Foundation, the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, Cure Cancer Australia, the Australian Cancer Research Foundation and the Victorian Government.

More News Articles

View all News